Toward Consistent Auditing of AI: OpenAI alumni found Averi to set standards for AI model audits

AI is becoming ubiquitous, yet no standards exist for auditing its safety and security to make sure AI systems don’t assist, say, hackers or terrorists. A new organization aims to change that.

AI is becoming ubiquitous, yet no standards exist for auditing its safety and security to make sure AI systems don’t assist, say, hackers or terrorists. A new organization aims to change that.

What’s new: Former OpenAI policy chief Miles Brundage formed AI Verification and Research Institute (Averi), a nonprofit company that promotes independent auditing of AI systems for security and safety. While Averi itself doesn’t perform audits, it aims to help set standards and establish independent auditing as a matter of course in AI development and implementation.

Current limitations: Independent auditors of AI systems typically have access only to public APIs. They’re rarely allowed to examine training data, model code, or training documentation, even though such information can shed critical light on model outputs, and they tend to examine models in isolation rather than deployment. Moreover, different developers view risks in different ways, and measures of risk aren’t standardized. This inconsistency makes audit results difficult to compare.

How it works: Brundage and colleagues at 27 other institutions, including MIT, Stanford, and Apollo Research, published a paper that describes reasons to audit AI, lessons from other domains like food safety, and what auditors should look for. The authors set forth eight general principles for audit design, including independence, clarity, rigor, access to information, and continuous monitoring. The other three may require explanation:

- Technology risk: Audits should evaluate four potential negative outcomes of AI systems. (i) Intentional misuse such as facilitating harmful activities like hacking or developing chemical weapons. (ii) Unintended harmful behavior such as deleting critical files. (iii) Failure to protect sensitive data such as personal information or proprietary model weights. (iv) Emergent social phenomena such as encouraging users to develop emotional dependence.

- Organizational risk: Auditors should analyze model vendors, and not just the models. One reason is to evaluate risks associated with variables like system prompts, retrieval sources, and tool access. For example, if an auditor treats a model with a certain system prompt as representative of the deployed system, and the system prompt subsequently changes, the risk profile also may change. Another reason to analyze vendors is to assess how they identify and manage risks generally. Knowing how a company incentivizes safety and communicates about risk can reveal a lot about risks that arise in deployment.

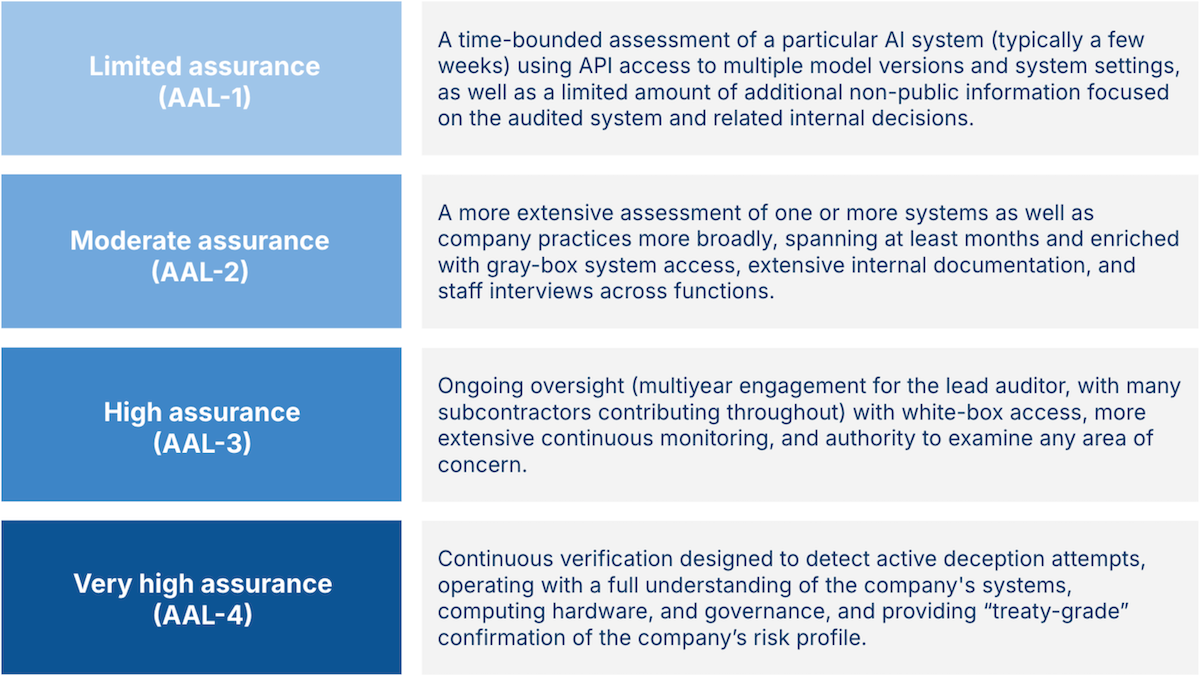

- Levels of assurance: Auditors should report a measure of their confidence, which the authors call AI assurance levels (AALs). They specify four levels, each of which requires greater time and access to private information. AAL-1 audits take place over a few weeks and use limited non-public information, AAL-2 takes months with access to further internal information such as staff interviews, and AAL-3 takes years and access to nearly all internal information. AAL-4, which is designed to detect potential deception, involves persistent auditing over years with full access to all internal information. The report urges developers of cutting-edge models to seek out AAL-1 audits immediately and receive AAL-2 audits, which would reveal issues such as negligence, differences between stated policies and actual behavior, and cherry-picking of results, within a year.

Why it matters: While the risks of AI are debatable, there’s no question that the technology must earn the public’s trust. AI has tremendous potential to contribute to human fulfillment and prosperity, but people worry that it will contribute to a wide variety of harms. Audits offer a way to address such fears. Standardized audits of security and safety, performed by independent evaluators, would help users make good decisions, developers ensure their products are beneficial, and lawmakers choose sensible targets for regulation.

We’re thinking: Averi offers a blueprint for audits, but it doesn’t plan to perform them, and it doesn’t answer the question who will perform them and on what basis. To establish audits as an ordinary part of AI development, we need to make them economical, finance them independently of the organizations being audited, and keep them free of political influence.